More evidence that low-calorie sweeteners are bad for your health

Studies show that artificial sweeteners can raise the risk of hypertension, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes and heart disease, including stroke.

Natural Health News — Adults and children in the US have been steadily consuming fewer daily calories for a decade – but there’s been no corresponding decrease in weight according to a new survey

The new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition summarises the findings of the nine National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) the CDC has conducted between 1971 and 2010. Several thousand adults aged 20-74 were randomly selected every two to four years and asked to recall what they ate over the previous 24 hours.

What they found was that among adults, average daily energy intake rose by a total of 314 calories from 1971 to 2003, then fell by 74 calories between 2003 and 2010.

Weight should be going down

In a recent interview with the Reuters news agency, William Dietz, former CDC director of Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity and co-author of the study said: “It’s hard to reconcile what these data show, and what is happening with the prevalence of obesity. Seventy-four calories is a lot … and we would expect to see a measurable impact on obesity”.

Indeed a deficit of 74 calories a day, all things being equal, should produce nearly 8 pounds (3.5 kilos of weight loss) over the course of a single year.

And yet in that same time-frame the percentage of women who are obese in the US remained steady at 35% and the percent of men who are obese rose from 27 to 35%.

According to Dietz obesity rates should have levelled-off for both sexes and to be decreasing at this point, if people are consuming fewer calories.

The CDC released similar results last month for children: boys have cut their daily calorie intake by 150, and girls by 80, since 1999. Nevertheless the pattern in weight is similar to that of adults with obesity rates for girls holding steady and rising amongst boys.

The CDC findings have produced a great deal of controversy amongst traditional doctors, scientists and nutritionists and some have criticised the way the data was collected.

Challenging the data

There are of course problems with data like this, which relies on people remembering what they ate. The current NHANES surveys indicates, for instance, that men take in an average of 1500 calories per day, and women 1800, for example. When doctors or nutritionists measure calorie intakes, they find an average of 3,000 for men and 2,400 for women.

Nevertheless, these same datasets have been used in the past as a reliable benchmark which experts have used to campaign for calorie reduction. These ‘experts’ can’t have it both ways according to whether the data agrees with their point of view or not.

But a calorie isn’t ‘just a calorie’

For a more helpful explanation for what’s going wrong, it’s worth looking at the work of endocrinologist Robert Lustig, author of the book Fat Chance: Beating the Odds Against Sugar, Processed Food, Obesity, and Disease, which deconstructs the mythology of fat. According to Lustig exercise, for all its benefits, won’t help you shed pounds and fasting only worsens weight gain.

Most importantly Lustig is on the leading edge of doctors who acknowledge that a calorie isn’t a calorie and accuses those who cling to this view of perpetrating a ‘big lie’.

In an extract from his book, published recently in the Huffington Post, Lustig gives four examples of how our bodies respond to the calories in different foods:

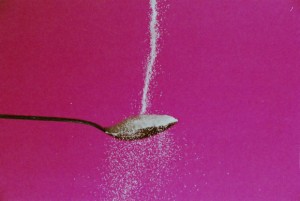

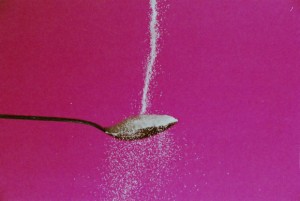

So we may be consuming fewer calories but if those calories are mostly sugar this could explain why we are not seeing any measurable impact on weight.

And of course none of these arguments, even touch on the notion of ‘chemical calories’ – the way that increased levels of environmental pollution cause our bodies to hold onto fat as a form of protection. Indeed a recent study has linked exposure to phthalates to obesity in children.

Its excess sugar, stupid!

In a recent analysis published in the journal PLOS One, Lustig and colleagues pieced together data from several sources to try and develop a coherent explanation for the exponential rise in diabetes worldwide.

They looked at data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAOSTAT), which measures food availability, the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), which measures diabetes prevalence, the World Bank World Development Economic Indicators, and the World Health Organization Global Infobase.

Their survey looked at total calories; meat (protein); oils (fat); cereals (glucose); pulses, nuts, vegetables, roots, and tubers (fibre); fruit excluding wine (natural sugar); and sugar, sugar crops, and sweeteners (added sugar). It also controlled for poverty, urbanization, ageing, and most important, obesity and physical activity.

Only changes in sugar availability explained changes in diabetes prevalence worldwide.

Lustig and colleagues survey found for instance that total calorie intake had little impact on diabetes prevalence; for every extra 150 calories per day, diabetes prevalence rose by only 0.1 percent.

However, if those 150 calories per day happened to come from a soda, (and Americans on average consume the added sugar equivalent of 2.5 cans of soda per day) diabetes prevalence rose 11-fold, by 1.1 %.

Lustig’s crusade against sugar is timely, given that New York City is still fighting a battle to ban super-size sugary drinks – a bold initiative that is ultimately for the health of its citizens. This restriction of ‘choice’ is being criticised as near treason in a society built on the premise that problems can be solved by allowing the ‘free market’ to sort them out, though the arguments for some kind of ‘choice editing’ of the foods in the marketplace are increasingly compelling.

In the mean time it’s a good sign that more people are willing to reducing the amount they eat. The next step is to ensure what they eat – and what they are encouraged to eat – sustains life rather than hastens its end.

Please subscribe me to your newsletter mailing list. I have read the

privacy statement